A new draft agreement for the UN climate conference in Glasgow on Friday presses countries to be more ambitious in their plans to tackle global warming, while walking a fine line between the demands of developing and richer nations.

While retaining its core demand for nations to set tougher climate pledges next year, the draft uses weaker language than an earlier text in asking countries to phase out fossil fuel subsidies.

It also lacks detail on future payments from the rich countries that are primarily responsible for global warming to the poorer countries that will take the brunt of worsening storms, droughts and floods and rising sea levels.

The new draft, which attempts to ensure the world will tackle global warming fast enough to stop it becoming catastrophic, is a balancing act - trying to take in the demands of climate-vulnerable nations, the world's biggest polluters, and nations whose economies rely on fossil fuels.

Campaigners and observers said the deal did try to ensure that countries take action, albeit not as fast as scientists have urged, to try to keep global warming within the 1.5 degrees Celsius seen as the threshold to catastrophic changes.

"This is a stronger and more balanced text than what we had two days ago," said Helen Mountford, a vice president at the World Resources Institute.

"We need to see what stands, what holds and how it looks in the end, but at the moment it's looking in a positive direction."

With the summit scheduled to end on Friday, negotiators have been working around the clock to try to clinch a deal that almost 200 countries can agree to - although many delegates expect the conference to spill into the weekend.

NEW PLEDGES

The COP26 conference has so far not delivered enough emissions-cutting pledges to nail down the 1.5C goal, so the draft asked countries to upgrade their climate targets in 2022.

However, it couched that request in weaker language than a previous draft, and failed to offer the rolling annual review of climate pledges that some developing countries have pushed for.

It said the upgrade of climate pledges should take into account "different national circumstances", a phrase likely to please some developing countries, which say the demands on them to quit fossil fuels and cut emissions should be lower than on developed economies.

The document also spelled out that scientists say the world must cut greenhouse gas emissions - mostly the carbon dioxide produced by burning oil, gas and coal - by 45 per cent from 2010 levels by 2030, and to net zero by 2050, to hit the 1.5C target.

This would effectively set the benchmark that countries' future climate pledges will be measured against.

FINANCE

Climate finance continues to be a stumbling block.

Poorer countries are furious that wealthy nations have still not fulfilled a 12-year-old promise to give $100 billion per year by 2020 to help them cut emissions and adapt to the worsening impacts of climate change.

The new draft expressed "deep regret" at the missed target, which rich countries now expect to meet in 2023, but did not offer a plan to make sure it arrives.

It did say that, from 2025, rich countries should double the funding they currently set aside to help poor countries adapt to climate impacts - a step forward from the previous draft, which did not set a date or a baseline.

It also broached the contentious topic of compensation for the growing losses and damage that climate change is inflicting on countries that had little part in causing it.

The draft pledges a new facility to address those losses, but does not specify if this would include new funding.

FOSSIL FUELS

The draft retained an explicit mention of fossil fuels, which if agreed would be a first for any UN climate conference.

But it qualified the previous text by saying the world should pledge to phase out "unabated" coal power - the dirtiest form of power - and "inefficient" subsidies for fossil fuels in general.

Arab nations, many of which are big producers of oil and gas, had objected to the wording of the earlier draft.

Jennifer Morgan, executive director of Greenpeace International, said that "the key line on phasing out coal and fossil fuel subsidies has been critically weakened".

But others were less concerned.

Bob Ward of the Grantham Institute at the London School of Economics said that "all subsidies for fossil fuels are inefficient".

And Chris Littlecott of the think tank E3G said the use of the term "unabated" would "call the bluff of the coal industry" by demanding that any power plants that were not shut down must pay for the technology to clean their emissions.

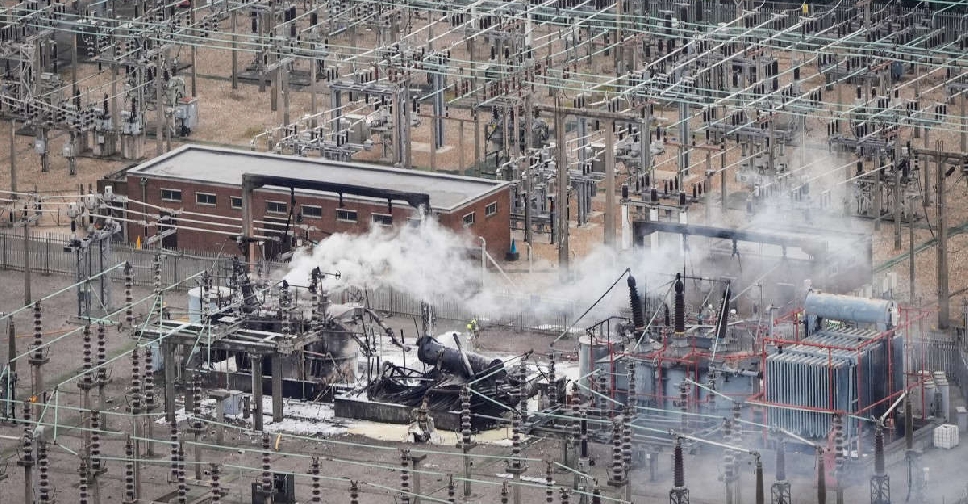

'Preventable' National Grid failures led to Heathrow fire, findings say

'Preventable' National Grid failures led to Heathrow fire, findings say

Trump urges Hamas to accept 'final proposal' for 60-day Gaza ceasefire

Trump urges Hamas to accept 'final proposal' for 60-day Gaza ceasefire

Iran enacts law suspending cooperation with UN nuclear watchdog

Iran enacts law suspending cooperation with UN nuclear watchdog

Two die in Spain wildfire, two deaths in France from European heatwave

Two die in Spain wildfire, two deaths in France from European heatwave

Paramount settles with Trump over '60 Minutes' interview for $16 million

Paramount settles with Trump over '60 Minutes' interview for $16 million